The lactase regulation mutation that spread most dramatically was in Europe, until by now it occurs in nearly the entire population of northwest European countries.

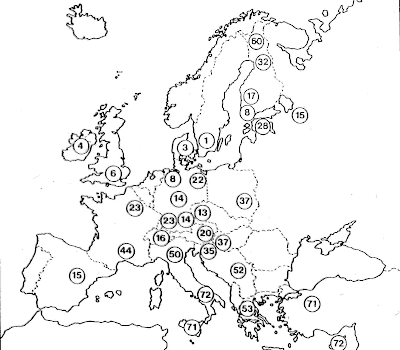

Modern frequency of lactase non-persistence as percent of the population in Europe.

Modern frequency of lactase non-persistence as percent of the population in Europe.This European lactase persistence allele soon came to be most concentrated along the Baltic and North Seas, what I call the core area of lactase persistence. Due to the heavy use of cattle in the core region, lactase persistence spread rapidly there, surpassing half the population by about 1500 BC.

The European lactase persistent populations played a substantial role in world history. The Baltic and North Sea coasts were the source of most of the cultures that conquered and divvied up the Western Roman Empire in the fourth through seventh centuries: Angles and Saxons (founded England), Ostrogoths and Lombards (Italy), Visigoths (Spain), Vandals (conquered north Africa), Frisians (the Low Countries) and Franks (France) among others. Later the lactase persistence core would produce the Vikings, who explored and conquered from Russia to North America and as far south as the Mediterranean, and the Normans, who invaded England, Sicly, and southern Italy led the Crusades among other exploits. Still later mostly lactase persistent populations would found the worldwide Portuguese, Spanish, French, Dutch and British empires and originate the agricultural and industrial revolutions.

Estimated spread of the European lactase persistence allele in the core region in northern Europe over time.

Estimated spread of the European lactase persistence allele in the core region in northern Europe over time.This was by no means the only gene evolving in the core. Indeed, the same cattle-heavy agriculture of northern Europe, probably originating in and migrating from central Europe, also gave rise to a great diversity of genes encoding cow milk proteins.

We found substantial geographic coincidence between high diversity in cattle milk genes, locations of the European Neolithic cattle farming sites (>5,000 years ago) and present-day lactose tolerance in Europeans. This suggests a gene-culture coevolution between cattle and humans. [ref]

(b) diversity of cow milk protein alleles, (c) frequency of human lactase persistence.

(b) diversity of cow milk protein alleles, (c) frequency of human lactase persistence.Associated with the lactase persistence core was a unique system of agriculture I call quasi-pastoralism. It can be distinguished from the normal agriculture that was standard to civilization in southern Europe, the Middle East, and South and East Asia, in having more land given up to pasture and arable fodder crops than to arable food crops. Nearly all agriculture combined livestock with food crops, due to the crucial role of livestock in transporting otherwise rapidly depleted nutrients, especially nitrogen, from the hinterlands to the arable. However, as arable produces far more calories, and about as much protein, per acre, civilizations typically maximized their populations by converting as much of their land as possible to arable and putting almost all the arable to food crops instead of fodder, leaving only enough livestock for plowing and the occasional meat meal for the elite. Quasi-pastoral societies, on the other hand, devoted far more land to livestock and worked well where the adults could directly consume the milk.

Quasi-pastoralism can be distinguished from normal, i.e. nomadic, pastoralism in being stationary and having a substantial amount of land given over to arable crops, both food (for the people) and fodder (for the livestock). A precondition for quasi-pastoralism was the stationary bandit politics of civilization rather than the far more wasteful roving bandit politics of nomads.

Compared to the normal arable agriculture of the ancient civilizations, quasi-pastoralism lowered the costs of transporting food -- both food on hoof and, in more advanced quasi-pastoral societies such as late medieval England, food being transported by the greater proportion of draft animals. This increased the geographical extent of markets and thus the division of labor. England and the Low Countries, among other core areas, gave rise to regions that specialized in cheese, butter, wool, and meat of various kinds (fresh milk itself remained hard to transport until refrigeration). A greater population of draft animals also made grain and wood (for fuel and construction) cheaper to transport. With secure property rights, investments in agricultural capital could meet or exceed those in a normal arable society. The population of livestock had been mainly limited, especially in northern climates, by the poor pasture available in the winter and early spring. While hay -- the growth of fodder crops in the summer for storage and use in winter and spring -- is reported in the Roman Empire, the first known use of a substantial fraction of arable land for hay occurred in the cattle-heavy core in northern Europe.

England's unprecedented escape from the Malthusian trap (click to enlarge).

England's unprecedented escape from the Malthusian trap (click to enlarge).Hay, especially hay containing large proportions of nitrogen-rich vetch and clover, allowed livestock populations in the north to greatly increase. The heavy use of livestock made for a greater substitution of animal for human labor on the farm as well as for transport and war, leading to more labor available for non-agricultural pursuits such as industry and war. The great population of livestock in turn provided more transport of nitrogen and other otherwise rapidly depleted nutrients from hinterlands and creek-flooded meadows to arable than in normal arable societies, leading to greater productivity of the arable that could as much as offset the substantial proportion of arable devoted to fodder. The result was that agricultural productivity by the 19th century was growing so rapidly that it outstripped even a rapidly growing population and Great Britain became the first country to escape from the Malthusian trap.

There are thus, in summary, deep connections between the co-evolution of milk protein in cows and lactase persistence in humans, the flow of nitrogen and other crucial nutrients from their sources to the fields, quasi-pastoralism with its stationary banditry and secure property rights, and the eventual agricultural and industrial revolutions of Britain, which we have just begun to explore.

No comments:

Post a Comment